By Carley Knapp, Bethlehem Farm Volunteer

One of my favorite aspects of being on the volunteer staff of Bethlehem Farm in Pence Springs, West Virginia, is the opportunity to lead crews of high school and college students in our gardens. We have two large gardens and several smaller ones where we cultivate many of the vegetables and herbs that we serve year-round during our service retreats. We host volunteers from schools, parishes, and universities around the Northeast, Midwest, and Central United States, and most of the young adults have not spent much time growing any of their own food. A transformation happens frequently that fills me with hope and joy: Students who at the beginning of the week seem tentative and uncomfortable with garden work by the end of the week are outside with wheelbarrows and pitchforks, big grins and dirty gloves, weeding, seeding, or layering on compost like they’ve been farming their whole lives.

I know when I get my hands dirty in the garden, it’s happy work that makes me feel a sense of connectedness. After all, I am connected to the soil if my food is growing there, not in an abstract kind of way but as a micro-biological reality. The adage, “You are what you eat,” links us through plants to the soil. We can only be as healthy as the food that we eat, and the plants that become our food can only be as healthy as the soil that feeds them. Just as humans enjoy a variety of foods and have individual culinary preferences, plants thrive in environments with a variety of bacteria and fungi and have unique nutritional needs. The problem is that most of the world’s soil today is eroded and degraded. A 2006 study in the Journal of the Environment, Development and Sustainability found that soil is being washed and swept away 10 to 40 times faster than it is being replenished. Our industrial society has not found a way to replace what it takes from the soil.

Pope Francis sums up this issue in Laudato Si when he writes,

It is hard for us to accept that the way natural ecosystems work is exemplary: plants synthesize nutrients which feed herbivores; these in turn become food for carnivores, which produce significant quantities of organic waste which give rise to new generations of plants. But our industrial system, at the end of its cycle of production and consumption, has not developed the capacity to absorb and reuse waste and byproducts. We have not yet managed to adopt a circular model of production capable of preserving resources for present and future generations. (Paragraph 22)

Nourishing our soils is one way to correct the wasteful patterns we have inherited in our society. If you have a garden, give it love in the form of lots of mulch and compost. If you don’t have a garden, give your food waste to someone who composts and gardens. Or start a garden! Worm bins are a great way to get quick compost from small amounts of food waste. At Bethlehem Farm, we even have a “humanure” system where we use sawdust and buckets to compost our own – you guessed it. Do what makes sense for you, just don’t forget about the soil.

Carley Knapp earned her Bachelor’s degree from Indiana University, and a Master’s in Theology from St. Meinrad Archabby. She now serves as a volunteer caretaker at Bethlehem Farm, located in Pence Springs, West Virginia.

This post is part of our new Justice Matters series, in which volunteers reflect on the social justice issues that have become an important part of their service experience.

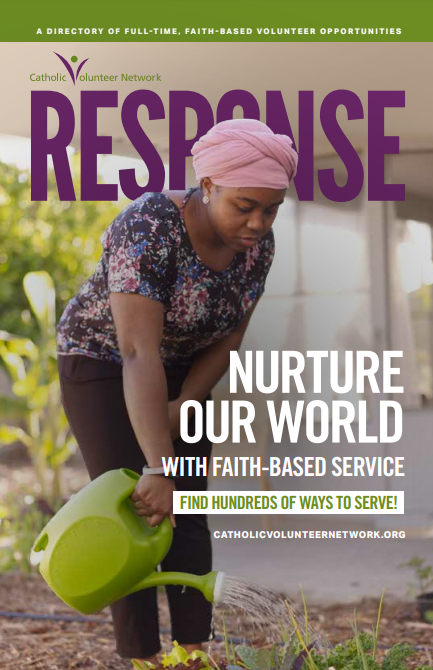

Thousands of faith-based service opportunities can be at your fingertips with the RESPONSE. Download the latest edition today!

Thousands of faith-based service opportunities can be at your fingertips with the RESPONSE. Download the latest edition today!