By Matthew Junker, Father Beiting Appalachian Mission Center

When I was an atheist, I liked to say that prayer is selfishly asking for every atom in the universe to be rearranged just for your own interest. Having mocked it for so long, I had a very difficult time with prayer when I came into Christianity. Unwilling to be completely vulnerable, my first response was to intellectualize it. I bought a book of prayers originally intended for seminarians and poured over the writings of Augustine, Catherine of Siena, the Little Flower, and other great spiritual teachers. But despite the beautiful prose, these prayers meant little when read as poetry or fragments of theology. This kind of intellectualization was a cautious half-step into the spiritual life, and although it kept the door propped open, I had yet to experience the full richness of prayer.

This half-stepping didn’t last long after coming to eastern Kentucky to work with the Father Beiting Appalachian Mission Center. Together, we pray at the beginning of each day in our chapel. We pray before each meal, and we pray at the beginning and end of each work day with those we serve. People here don’t shy away from displaying their faith, and it wasn’t long before others began asking me to pray for them. By friends and strangers alike, almost everyday I’m asked by someone new to keep them in prayer. It’s easy to see that these kinds of requests aren’t just pleasantries. When people here ask for prayer, they really mean it, and I knew if I was going to be honest, I had to follow through. As the director here said to me one day, “there’s nothing worse than saying you’ll pray for someone and not doing it.”

This kind of religiosity is so often mocked in the wider culture. The tragedy is that this hostility isn’t just out of disagreement, but out of a profound misunderstanding of what faith actually is, a misunderstanding that deepens as our societal literacy in philosophy and the liberal arts slowly deteriorates. Prayer seems ridiculous if one is expecting the miraculous regression of tumors or the sudden reappearance of sight, as some televangelists might promise. But seldom do we encounter God in this way. Rather, we find God in the passion and intelligence of those advancing medical science. We find God working through healthcare practitioners who turn down offers with higher pay in order to serve those with greater need, and we find God in the sacrificial love of friends and family when illness strikes.

Despite poverty, illness, and all of the other reasons here for people to lose trust in God, I’ve encountered a people of relentless faith. The passion of the kids in our youth program, of the community leaders I’ve met working at the food pantry in town, and of my neighbors while visiting them in their homes has acted like a mirror to point out those shallow areas of my own spirituality. Their faith does not weaken because they recognize God everyday in the face of good neighbors and loving families. They see God acting through the hundreds of people who, despite having every reason not to, choose to come here anyway to swing hammers and dig ditches. And most importantly, they see God in themselves as they muster the strength to press on. Although these encounters are more commonplace, they are no less extraordinary than miraculous healings. In fact, the regularity of these encounters is what makes them so extraordinary – that we are continually brought back to love in a world filled with great darkness.

During my time with the Mission Center, I have learned that prayer is not just an intellectual exercise, some sort of meditation on metaphysical reality. Prayer is not passive; it is a generative act that strengthens our spiritual bond. As social and economic divisions grow, prayer asserts our radical equality before God. We are brought together to the common table where we learn to see the world from others’ shoes and to recognize each other’s value as uniquely-created and equally-treasured beings. We see darkness spreading by dividing and conquering. We pray so that we can tear down these walls and strengthen our spiritual solidarity, so that, together, we can walk that righteous path toward liberation.

My time in Appalachia has taught me to come down from my head and into my heart, and out from my heart into my hands. We do not pray because we expect sudden intervention from on high. We live in a world of great abundance, overflowing with talent, skill, intelligence, natural resources, and everything else we could possibly need to build a world that benefits all. The only element we lack is love. This is why we pray – to strengthen our ability to love, that deep, sacrificial kind of love that no other power can stop. The kind of love that heals wounds, uproots oppression, and builds anew. I pray so that I may love, so I must come to love to pray. This is what I have learned volunteering alongside the people of Appalachia.

To learn more about Father Beiting Appalachian Mission Center, please click here.

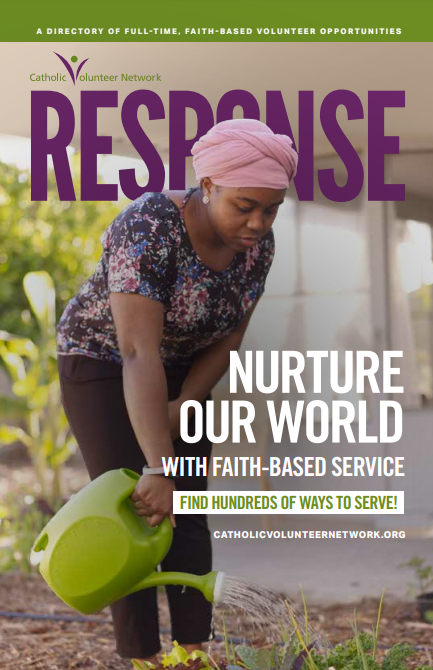

Thousands of faith-based service opportunities can be at your fingertips with the RESPONSE. Download the latest edition today!

Thousands of faith-based service opportunities can be at your fingertips with the RESPONSE. Download the latest edition today!