By Zach Wiley, Bon Secours Volunteer Ministry

In his book The Great Divorce, C.S. Lewis paints a picture of purgatory as a dreary, sprawling, abandoned town in which no one can stand being around each other, so they keep moving away and out, further and further away from contact with others. They do not move away from each other out of fear, but rather out of a profound inability to coexist and understand the emotions and needs of others. This applies startlingly well to our daily lives. I think of all the times I have automatically avoided eye contact with the man asking for money on the corner, or remained oblivious to the needs of neighbors, friends, and even family. The conscious decision to develop community is the opposite of this; it is the decision to live closely with others, accepting the occasional frustration and discomfort that this causes for the joy and sense of belonging that living in community brings.

Community is a necessary part of the human condition. For most, the first community we know is family, which then extends gradually outward to extended family, neighborhood, church or parish, town, city, state, and nation. Many senses of community extend even beyond the nation, an example being the international and worldwide community of the Church. Members of a community are tied together by shared history, experience, place, belief, and often all of the above at once. Seeing as community is so essential to all of us, it is no wonder that it plays a large role in our religious ceremonies and beliefs. For example, as Christians we worship together, and we celebrate important events such as marriage and baptism not solitarily, but surrounded by members of our community. Therefore, one could say that community has an important interaction with religious belief, both supporting it and being supported by it.

In modern America many communities are hurting and broken. We see this most visibly in our neighborhood in West Baltimore. Abandoned houses and churches stand as testament to families and faith communities that used to be here, but no longer are. This is not to say that no one lives or goes to church here, because people still do, but simply to show that these community ties have weakened. And this is not constrained to inner city neighborhoods: communities across the country, rich and poor, are suffering from poverties and addictions. From what I have seen, I believe that these maladies are all intricately connected to the health, or lack thereof, of community ties and support. That is, communities are weakened when members, through no fault of their own, are struggling to survive financially, emotionally, or spiritually, and weakened communities are then less able to respond to the demands caused by these challenges. Additionally, becoming a part of a strong community offers more than just material and emotional support: learning to live and empathize with others is instrumental in one’s spiritual growth and relationship with God. Drawing closer to community draws one closer to God, and therefore a rightly ordered community is a glimpse of Heaven on Earth. Reflecting on the Lenten season that recently ended, I realized that there is a commonality between Lent and community life: both involve challenging the self in order to become closer to God.

When I applied to Bon Secours Volunteer Ministry I was excited about developing community, for its importance in sharing experiences and creating a support network. In the months since I arrived in Baltimore, my understanding of what developing community really means has been broadened and deepened substantially. I have had to adjust some of my own habits and ways of thinking, as have all members of our community. This adjustment to community life, and the discomfort that goes along with it, allows one to arise to new life in community. I have learned that challenges are an inherent part of a community, but that divisiveness is not. I have learned that being nice is shallow and that it is preferable to be kind and direct. Most importantly, community living has given me the space to learn these lessons on a small, personal scale and prepared me to bring these lessons to service in our neighborhood.

Consider an analogy: God’s love sustains a small flame in us. When we do service, we are trying to share the light from the candle with others and to brighten up the darkness in the world. We want to share this light as much as we can, but the world is windy and makes the flame flicker. This is especially true when a person or situation makes it difficult for me to feel empathy. My service site in the Emergency Department of the Bon Secours Baltimore Hospital presents experiences on a daily basis thatmake empathy difficult. The challenging nature of the cases we see, (drug overdoses, assault victims, and patients with chronic disease) creates an environment in which the presence of God at times feels weak. Living in intentional community provides practice in sharing empathy, which prepares us to better extend this empathy to patients.

To return to our analogy, the flame becomes brighter and stronger through practice. This means that we become closer to God, in that He dwells in us more strongly, the more we share this light. As each community member individually draws strength and peace from God, the love that we share provides the presence of God to each other. In learning to see God in the members of our intentional community, we practice and strengthen our ability to see the presence of God in the people that we serve. When we ground ourselves in small scale community we are better able to participate in our broader community, especially our neighborhood, but also our cities, states, and country. My community has been an important part of my volunteer experience, serving as an expression of God’s love for me, and as a source from which I draw love and light.

To learn more about service opportunities through Bon Secours Volunteer Ministry, please click here.

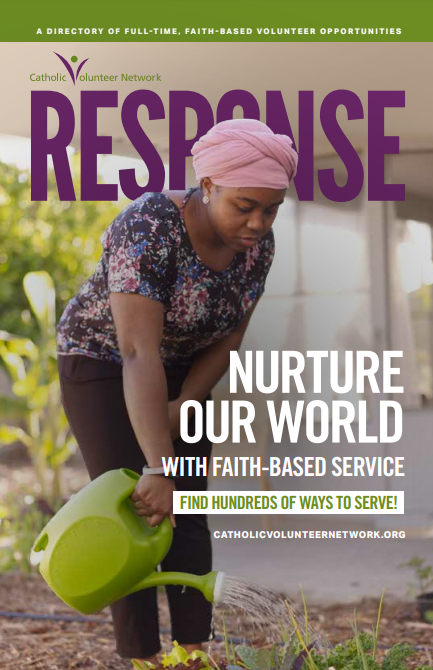

Thousands of faith-based service opportunities can be at your fingertips with the RESPONSE. Download the latest edition today!

Thousands of faith-based service opportunities can be at your fingertips with the RESPONSE. Download the latest edition today!