By Kevin Donohue, Fairfield University Campus Minister and Passionist Volunteers International Alum

Part of the challenge of a year of service is that it takes place within a very discreet and limited time span, but the impact on the volunteer is supposed to last much longer, conceivably for the rest of their life. This is difficult because within the confines of that year, it’s hard to envision how the sometimes intense lifestyle of volunteering is ultimately going to matter over the course of one’s life.

Early in my year of service with Passionist Volunteers International in Jamaica, this was a concern I had often. I spent a lot of free time at our neighbors who had internet access, looking at job listings back at home, and wondering how my experience in bringing elderly Jamaicans the Eucharist would make me eligible for any of the interesting positions I came across. To quote Aventureland, a favorite movie of mine, “What am I supposed to do, I’m not even qualified for manual labor?”

My time volunteering was a great blessing, but it was also the hardest thing I’ve ever done. I was scheduled to be in Jamaica for twelve months, and, early on, I would often find myself in the bad habit of counting down the time I had left, both with a sense of anticipation and with dread. I knew I didn’t know what I’d do upon coming home, but I also knew how lonely I sometimes felt, and how exhausting it could be to live in a country with such a different culture like Jamaica.

Sometime in February, about half way through my time in Jamaica, I had a big turning point. I was vaguely thinking over my plans for the rest of the week, and in the back of my mind I started to calculate how much time I had left in Jamaica. Without giving it too much thought, I simultaneously realized that I didn’t know and didn’t care. It quickly dawned on me that this was really significant. I wasn’t going through my year of service with an eye towards what it would eventually mean. I was doing my year of service. I wasn’t just staying in Jamaica, I was living in Jamaica. This was by no means all of a sudden easy to do, but I knew I was happy and grateful and able to do it.

Fast forward about 18 months. Without any real plan, I moved to Washington DC in search of a job. I quickly realized that my lack of credentials or marketable skills were a sticking point for would be employers. In one day, I got rejected from three real, pride restoring, health insurance providing jobs. I did get one offer, which I had no choice but to accept, from a professional tennis franchise to work as a “Marketing Associate.”

It turns out that what they meant by “Marketing Associate” was dressing up as the team’s lovable mascot, Topspin. For a few months, I had to travel to local events in the DC area, put on my blue tights, 4-fingered cartoon gloves, and tennis ball torso, and try to build enthusiasm for mid-level tennis. At one memorable outing to a Washington Capitols hockey game, I almost got into a physical altercation with a fan who was getting a bit too aggressive with ‘ol Topspin. I can’t say for sure what I had in mind when I moved to Washington, but I can say definitively it was not that.

Needless to say, this time was rough. I was totally demoralized, working in a humiliating job that barely covered my Ramen noodles bills. With all of that weighing on my mind, I was most discouraged by the factI couldn’t figure out how I was going to get out of my predicament. I would desperately search for jobs, but nothing came through, and there seemed to be no light at the end of the tunnel. All I could think about was taking the next step, but it is hard to be upwardly mobile when you’re inside of a bulky tennis ball costume.

One day, I was at an event with a friend. It was his turn to be Topspin that day, to my overwhelming relief. In the midst of giving thanks that I was off the hook, I noticed that there was something strange about my friend’s demeanor that I couldn’t understand. Not only was he not disgusted to be dressing up as a tennis ball, he actually seemed to be enjoying it. He was running around with kids, he was dancing to music, and he was generally having a good time. Whenever I was Topspin, despite the huge grin on the face of the tennis ball, you could always tell that the person inside was miserable. When my friend was Topspin, he seemed to be a person who’d make you come and watch some tennis. Weird, right?

The video at the top of this post was taken of me shortly after that day. If you can’t tell, I’m actually enjoying myself inside of the suit. After months of resenting the fact that I worked as a mascot, I finally allowed myself to have a little fun with it. For a few minutes, I put my desperate search for a real job on pause, and embraced the moment I was in. I was the Tennis ball.

Since returning from Jamaica, I’ve relied upon my experience of service in a million ways, both as a Campus Minister (a job I eventually got after my time as Topspin had come to an end) and in personal situations; none of which I could have foreseen or understood before actually going through that experience. Similarly, despite my embarrassment about it at the time, I value my time in working as a mascot. It has helped me to never take myself too seriously, and reminded me about how irreplaceable persistence is.

These are all lessons I learned only by embracing the moment, which is something I still struggle to do. For all of you out there are who are doing a year of volunteering, or thinking about doing one, it can be easy to fret over how your powerful, scary, confusing experiences will ultimately fit into your lives. To a degree, it is important to keep these things in mind in order to prepare for a successful and fulfilling career and life. However, the path will never be clear or straightforward. If you ever find yourself too overwhelmed with worry about what the next step will be, do your best to embrace the moment and just do what you’re doing. Be the Tennis ball.

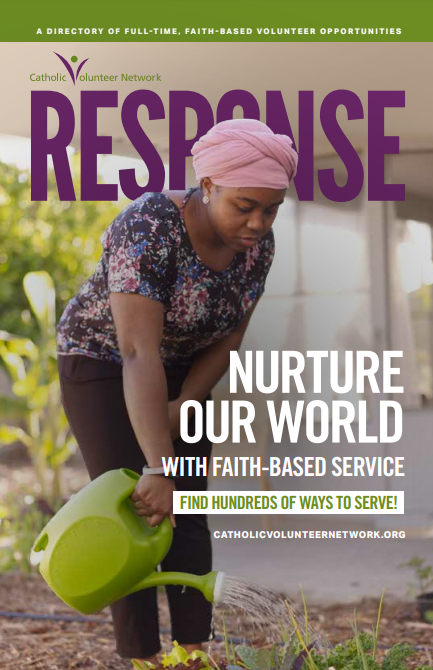

Thousands of faith-based service opportunities can be at your fingertips with the RESPONSE. Download the latest edition today!

Thousands of faith-based service opportunities can be at your fingertips with the RESPONSE. Download the latest edition today!