By Annemarie Barrett

Current missioner in Bolivia

with Franciscan Mission Service

Living in the city, shopping at grocery stores, and watching a lot of TV, I never had to think much about how my food arrived at my table. I could answer that easily, “From the grocery store.”

But how did it get to the grocery store?

In high school I was blessed with the opportunity to attend POWER Summit, a small youth summit in Saint Paul, Minnesota, hosted by Celeste’s Dream a youth ministry sponsored by the Sisters of Saint Joseph. It was the first time that I was invited to think about where my food came from and the first time I met people growing their own food.

But it was not until living as a Franciscan lay missioner here in Cochabamba that I really started to share daily life with people and whole communities who came from farming families, to work side by side with people who have grown up connected to the land.

It was then that I realized that my television never got around to teaching me about plant recognition.

I had never seen a turnip in real life.

I did not know the difference between an apple tree and a peach tree. I did not know the first steps in planting a seed.

|

| A woman in Santa Rosa with the tomatoes she produced in her home garden. |

Living disconnected from the land, it was easy to laugh at tree huggers and other stereotypes, really because I had no idea what it might feel like to care enough about a tree to hug it. Why would you do that? My cell phone cares for me, sure, but a tree? I did not get it. I am exaggerating, but you get the point.

Then I met Casta, my Bolivian boss in the garden who was raised in a farming family. I listened to her talk about caring for the garden in her home. She spoke about each plant with affection, like it was her own child or friend.

She invited me to work with her, caring for the plants in the parish garden. I spent many days weeding and digging and watering. And little by little, I started to understand.

Through contact with the land, I woke up to the mutuality; the relationship one can form with the plants, as they live and breath just like us, as they nourish us while we nourish them.

|

| Meal prepared in one of the homes in Santa Rosa. |

In connecting to the land as a mother, it became harder and harder to imagine using chemicals in our work. The more I learned about how plants and trees are both delicate and resilient, just like us, I became more careful of where I walked in the garden, aware that I was walking through a space filled with living beings, not products to be consumed and thrown away.

And the women in Santa Rosa taught me as well. They pointed out all the little seedlings in their home gardens. They invited me to meals made with the fresh vegetables they produced. And they still make fun of me for not being able to adequately plant potatoes.

Did you know that in the campo you need to know how to plant potatoes well before you can think about getting married? Because in the campo you produce food and income for your family, so you need to know how to produce to be able to start a family. I did not know, but these women have taught me.

And it makes sense, doesn’t it?

|

| Harvesting potatoes in the parish garden. |

If we live connected to the Earth, we realize that we depend on her just like she depends on us. When our food depends on our harvest and not the supermarket, we learn to respect the cycles of the soil, the seasons and the production. We learn to live in relationship to our Mother Earth and the people that work her land.

And as a Franciscan lay missioner, I have learned that solidarity in practice here means sharing work with these marginalized farming communities, valuing their culture and their wisdom, choosing to learn from them and their connection with the Earth. Recognizing that my reliance on imported food, corporate controlled food systems, and contamination producing large city living is unhealthy for both me and my community, local and global.

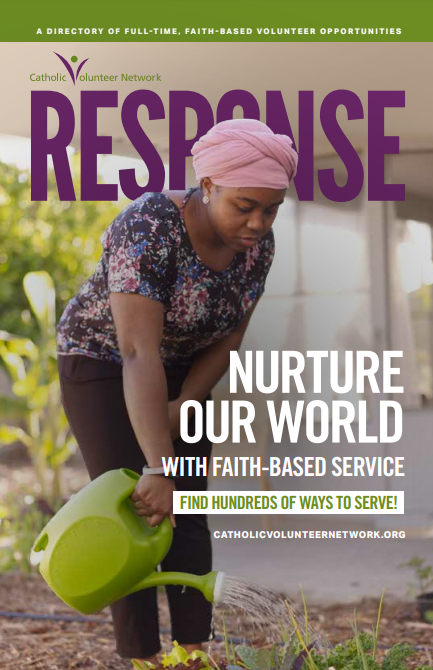

Thousands of faith-based service opportunities can be at your fingertips with the RESPONSE. Download the latest edition today!

Thousands of faith-based service opportunities can be at your fingertips with the RESPONSE. Download the latest edition today!