By Kevin Chung, Jesuit Volunteer Corps

My perspective on social justice used to be that no matter whether a person is white, black, Asian, Hispanic, etc., they should receive the consequences for breaking the law. My college friend would always tell me that my perspective on social justice shouldn’t be that simple, because of the systematic racism that people of color face. I disagreed.

I grew up in Los Angeles, California. Although the city is diverse, I grew up mostly with whites, and I moved to predominantly white Portland, Oregon for college. So moving to Newark in order to serve at Covenant House as a Jesuit Volunteer was a culture shock because the population I worked with was between the ages of 18-21, homeless, and predominantly black and Hispanic.

I assumed that because the clients’ age range, many of their existential issues would concern housing, but also around who they are, what they wanted to do with their lives, and about their dreams. But I was wrong. My perspective on the world was rocked hard in the first month I worked there. The youths were all fantastic and had amazing talents, whether it was through their artistry, academics, or a whole myriad of other things. That being said, they still had challenges that they faced every day.

There were too many noble youths who changed my life to mention in one reflection, but I will say that I worked with youths who dealt with drug addiction, abuse in every shape and form, being trafficked, who were mentally disabled, and ultimately were not only hurt by their parents and guardians, but also by the world they lived in.

In the beginning, I kept thinking, if they knew to focus on their education or if they would do this or that, then their lives would be so much better. In my reality, it wasn’t so complicated to imagine “what they should do,” because if I were in their shoes, I’d know what to do.

Soon it hit me. Their reality was completely separate from mine. In my reality, education meant empowerment, and potentially a good career. For many of my youths, education might have meant nothing. Their focus was often immediate survival, learned during upbringing, a skill that could potentially get them in trouble with the law. But what affected me was that the very systems in place that are supposed to help these youths are also the systems that are placed for them to fail.

That’s when I realized that the systems in place aren’t fair because they oppress the people who are already ignored and therefore invisible, thus adding thickness to that invisibility. But what hurt the most was that these youths were too young to have experienced the pain they faced. It just wasn’t right.

Eventually, I was hit with a feeling of hopelessness. What was I able to do? I was only a JV. I didn’t have the answer, and just decided that all I could do was perform my job to the best of my ability. I was mostly in charge of programming, so I made sure all of them were effectively planned and executed. I eventually saw that these youths slowly became empowered and started to feel a sense of community.

Through an art class I supervised, I worked with a youth who is an amazing artist to create a mural in the art room by covering the walls with paper. The youths were able to paint whatever they wanted, and the room was packed as they expressed themselves onto the wall with each other.

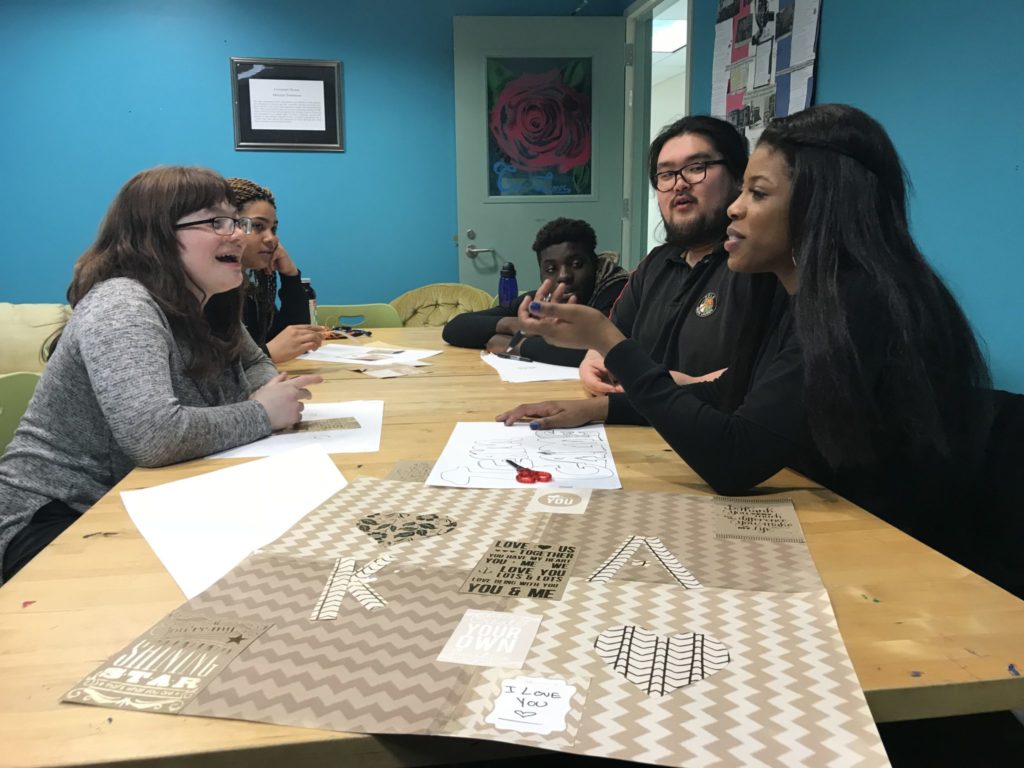

I ran a philosophy discussion group and I taught them about some of the greatest thinkers, while also using their teachings to empower the youths. I taught them about Martin Luther King Jr., Nina Simone, Toni Morrison, the Black Panthers, Leibniz, Heidegger, Marx, and Nietzsche in order to show them that they can use their talents to help contribute to social change.

Kevin (Second from Right) leading philosophy discussion

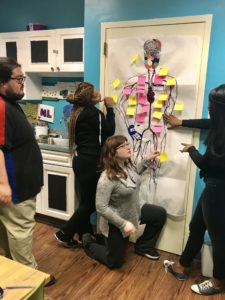

I co-lead an ethics class that taught the youths moral reasoning, in order to help them think about their moral stance and their beliefs. I directed a group called peer advisory, which was a youth led group that focused on practicing mindfulness, in order for the youths to take the positivity from the session for the rest of their day. In one session we displayed a poster of a human being, and they wrote the meanest comment they received on a sticky note and placed it on the human being, but after, they wrote the kindest comment they received and placed it over the mean comment.

Slowly and surely, I felt something, and it was a feeling that although I could not do everything, I was able to do my part to the best of my ability, while also praying to the universe to do the rest.

The JVC house I lived in was called the Oscar Romero House. I never saw any significance in that until one night, while in the first floor bathroom, I read a quote by Romero that was taped to a wall, that I read repeatedly before. But this time, it touched me: “We cannot do everything, and there is a sense of liberation in realizing that. This enables us to do something, and to do it very well. It may be incomplete, but it is a beginning, a step along the way, an opportunity for the Lord’s grace to enter and to do the rest.”

It reminded me that I cannot do everything, but there’s comfort in that. I believe that as long as I do the best I can in the role I am given, then I’m doing the most I can. One such rewarding moment came when a youth and I shared an intimate moment that I will treasure forever. He was always resistant to affection, especially when other staff members and I would tell him how much we believe in him and when we would say “I love you.”

One day, he came up to me to give me a hug, and he was poking fun at me. As I was walking away, I heard him say, “I love you.”

Kevin (Left) leading youths in a mindfulness activity

From this experience, one thing I’m walking away with is that there’s no way I can, in good conscience, pursue a career that does not somehow contribute to social change. I plan on pursuing psychiatry because I believe behavioral health is the most important aspect for anyone who’s been beaten by the world to heal. And I thank not only God and my mentor Dr. Thoits, but also the youths of Covenant House for teaching me about love, strength, and social justice.

The Staying Connected newsletter is made possible through the partnership of Catholic Volunteer Network and Catholic Apostolate Center.

Thousands of faith-based service opportunities can be at your fingertips with the RESPONSE. Download the latest edition today!

Thousands of faith-based service opportunities can be at your fingertips with the RESPONSE. Download the latest edition today!