Allie is one of five CVN Serving with Sisters Ambassadors – volunteers sharing the joy, energy, and fulfillment of serving alongside Catholic Sisters in CVN member programs, through creative reflection, conversation, and experience. Enjoy this post, and stay tuned to hear more from Allie and her fellow Ambassadors over the course of their service year!

|

| Our new “frenemies,” the parrots, at the Mariposario in Santa Cruz, Bolivia. |

The sound of a parrot mimicking its sounds at a sheep, who “bahs” back, is my alarm clock every morning around 6:30 AM. I get out of bed, go to the bathroom, and check for water. I turn the faucet handle – no water. This is the outcome at least three times a week. I know this means I have to use the bucket of water, which my community member, Andrea Gaitan, and I fill on other days when we are privileged with water. We use this bucket to brush our teeth, wash our hands, fill the septic tank so we are able to flush the toilet, clean clothes, our faces, floors, and walls, and to boil for drinking water. The water is not safe to drink from the sink, which leads us to spend our Sunday nights recycling the water bottles we acquired from the week before to fill them with boiled, healthy drinking water for our upcoming week. Starting our mornings in this discouraging way can lead me to think: why did I choose this life? Why did I choose to live in a place where the water is not safe to drink, and the air is so thin from the 9,000 ft. altitude that I lose my breath going up stairs?

As these thoughts and questions cross my mind after leaving our apartment, we enter a bus, paying the driver 1.50BS (Bolivianos) for the ride. The journey to work takes about 30 minutes, as we pick up many children catching a ride to school. As the ride continues, it gets very crowded with people hanging out the door and windows. You quickly learn there are no bus stops or stop lights. This leads to the honking language heard everywhere; HONK from the taxi to let you know they are available, HONK HONK from the car going through the intersection to let other cars know they are there, HONK from a car while you are walking on the side walk so you know not to cross the street at that time. “Vamos a bajar,” we tell the driver as we come to our stop, to let him know we will be getting off. As we exit the bus, I’m still wondering why I left the world of luxury the United States easily provides. Then we enter our workspace, and I am answered with why I am here.

|

| One of the Sayariy Warmi participants making a scarf. |

We work at Sayariy Warmi, a name written in Quechua – an indigenous language that a majority of people here speak. Quechua is extremely different from Spanish, which can lead to difficulties in communication at times. Translated to Spanish, Sayariy Warmi means Lavantate Mujer, and roughly translated to English it means Rising Woman or Woman Rise Up. Sayariy Warmi is a place where women suffering from domestic violence can come claim their independence. The program provides classes ranging from sewing to computer skills, and I am currently helping the program create a group of women leaders to learn about women’s rights in politics. Andrea is working with the psychologist and helping with the social work of this program. I have spent most of my first month learning the language, politics, economics of my new country, and other various helpful skills in order to do my job. Because I am still learning Spanish, when I am presented with a woman who speaks Quechua the communication level becomes even more difficult.

|

| Andrea (left) and I exploring Santa Cruz, Bolivia. |

While learning about my job, the work environment in Bolivia has proved to be quite the opposite from the work place in the United States. Here, there is not always internet, sometimes there is no water, with transportation difficulties people tend to be late (where as the United Sates culture is to try to arrive 15 minutes early), the lunch break is two hours long and the most important meal of the day, and every day around 3:00 PM it is cultural protocol to have tea and bread with jelly. Andrea and I are lucky to eat lunch with Sisters of the Good Shepherd every day. Working in different conditions than I am used to has taught me to be flexible, to understand that this is the way Bolivians know how to do their jobs, and that there is always a way to figure out how to do something in Bolivia.

While I am learning how to deal with new ways to work, there are also the communities we serve. Along with the women’s center, our other Sayariy Warmi communities are in various places. One is in a place called Barrio Bolivia, in the mountainside. These families live in tiny square houses with no water, electricity, or bathrooms. In order to own a house, the family has to have at least five children; I know of family who has a Mom, Dad, Grandma, and nine children sharing a home without basic necessities and different farm animals running around. In Barrio Bolivia we have a Comedor, dining room, for 47 children from the Chalice program to have a safe place to eat and complete their homework. Chalice is a program where families from Canada sponsor children to help provide for their needs. This dining room provides lunch and dinner, and other volunteers offer homework help and games.

A different children’s center, which also happens to be where Andrea and I live, provides an educational care center for other children of the Chalice program. Right now there are around 50 children ranging from ages two to eight who come every week-day from 8:30 AM to 4:00 PM – a day filled with different lessons, games, snack, lunch, and of course, tea time. These children are not always clean, might come from tight living conditions (most houses in this area have seven families in one building, with one bathroom to share), and might have to wear the same clothes day after day. It’s clear that they are poor. But, I learn so much from them as they generously share with me their tiny, fun personalities and laughter. Serving these communities helps me realize at the end of the day how lucky and blessed we are for the days we do have water and other little successes here, and for the life I have been privileged to live in the United States.

When I get home from my workday, I reflect on the day we just had. There are days where I feel a lot of anger, sadness and shock; other days are filled with success and joy. Either way my workday ends, it leaves me thankful for the way my life has been and wish we could do more for these families. It is hard for me to understand how at home in the United States, I can order a new pair of socks on Amazon Prime expecting them in the same day or the next without ever leaving the comfort of my bed, while these families walk miles to go to stores for basic necessities such as socks, water, food, school or any other thing you might think of. These people are working so hard just to live the simplest life. As my nights close with these new mind-boggling thoughts, they tend to end early as I go to sleep around 9:00 or 10:00 PM to be able to wake up to the parrot the next day, awaiting my next Bolivian adventure.

When I get home from my workday, I reflect on the day we just had. There are days where I feel a lot of anger, sadness and shock; other days are filled with success and joy. Either way my workday ends, it leaves me thankful for the way my life has been and wish we could do more for these families. It is hard for me to understand how at home in the United States, I can order a new pair of socks on Amazon Prime expecting them in the same day or the next without ever leaving the comfort of my bed, while these families walk miles to go to stores for basic necessities such as socks, water, food, school or any other thing you might think of. These people are working so hard just to live the simplest life. As my nights close with these new mind-boggling thoughts, they tend to end early as I go to sleep around 9:00 or 10:00 PM to be able to wake up to the parrot the next day, awaiting my next Bolivian adventure.

Allie, a current Good Shepherd Volunteer, will be blogging about her service experience as part of our ongoing Serving with Sisters Ambassadors series. This series is sponsored by CVN’s From Service to Sisterhood Initiative, a project made possible thanks to the support of the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation.

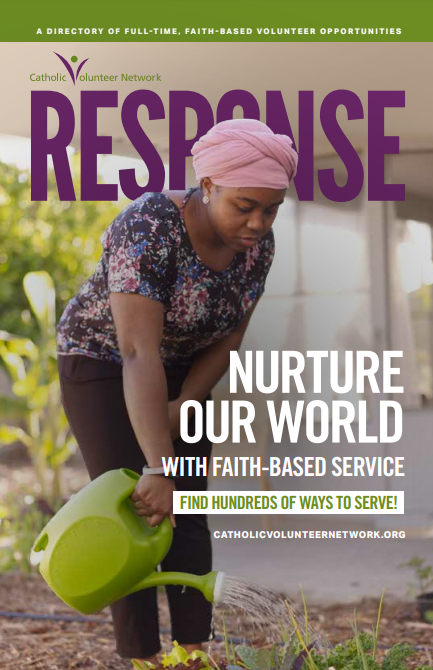

Thousands of faith-based service opportunities can be at your fingertips with the RESPONSE. Download the latest edition today!

Thousands of faith-based service opportunities can be at your fingertips with the RESPONSE. Download the latest edition today!